Cheng-Han Hsieh

Cheng-Han Hsieh

Research

Topic#1: Initial Mass Function

Mass is the most fundamental property of a star, as it determines its structure, evolution, and its fate. The Initial Mass Function (IMF), which describes the mass distribution of stars at the beginning of the main sequence phase, is the most important distribution in both stellar and galactic astrophysics. However, there is no current satisfactory theory for the origin of the IMF that can explain both the power-law tail at high masses and the mass at which the peak of the distribution occurs.

Research Highlight #1: Derived the first 2D Protostellar outflow rate maps

Recent STARFORGE simulations show that protostellar outflows can disrupt the accretion flow around the protostar, allowing gas to fragment and additional stars to form, thereby setting the peak of the IMF to a value similar to that observed. Protostellar outflows are believed to be the main mechanism that helps disperse the envelope surrounding the protostar (protostellar core), terminate the infall phase, and set the final masses of stars. However, in observational studies of outflows, one major unsolved problem is that the measurements of outflow mass rate, outflow momentum rate, and outflow energy rate (hereafter, outflow rates), which are important for envelope dispersal, are uncertain and highly scattered. This resulted in conflicting results even in recent surveys.

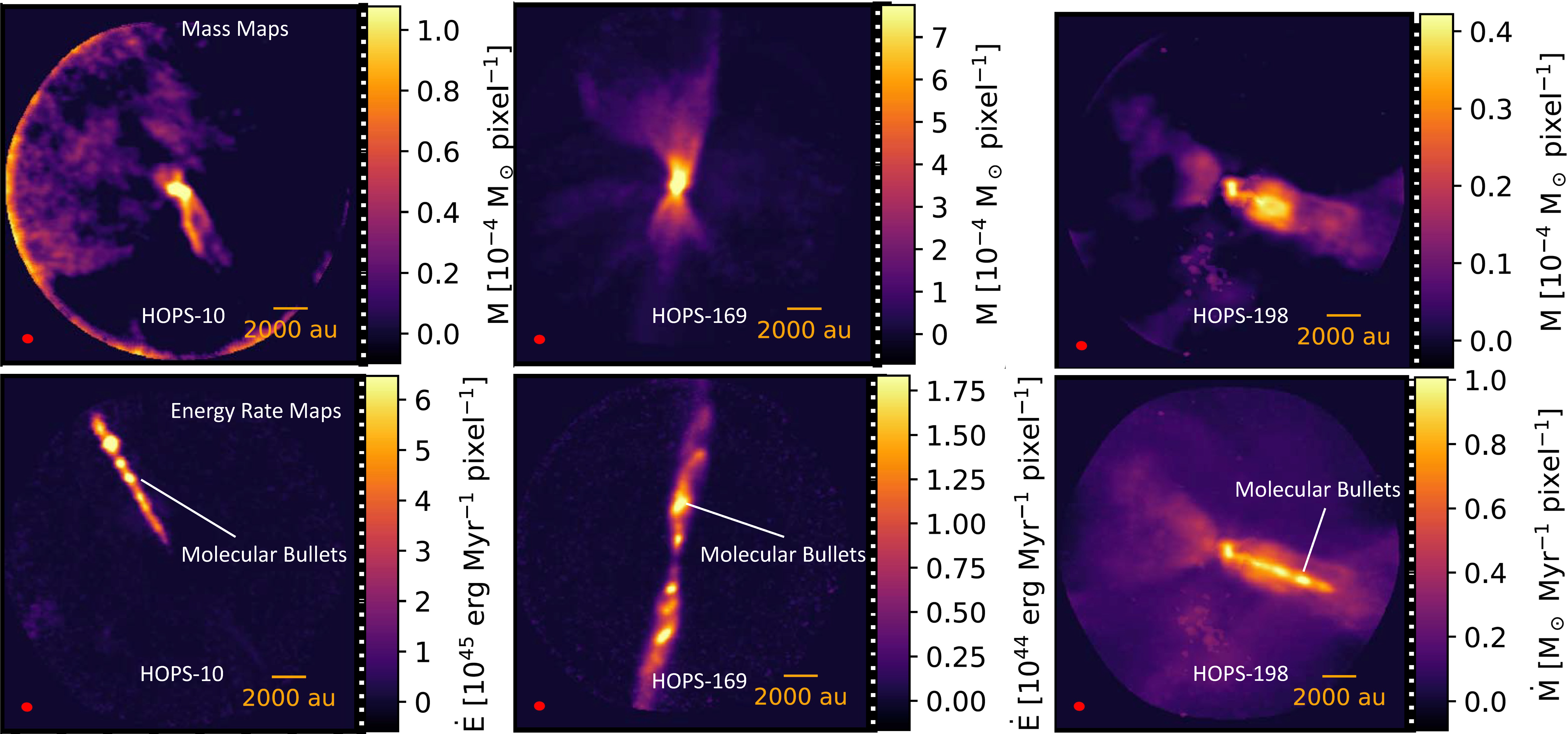

During my Ph.D., I investigated the widely used method of estimating outflow rates using a single dynamical time, spatially averaged over the whole outflow lobe, and found that it is unreliable. To better estimate outflow properties and their impact on their surrounding, I developed a new method, the Pixel Flux-tracing (PFT) technique to measure outflow mass, momentum, and energy ejection rates. The PFT technique allows us to compute two-dimensional molecular outflow instantaneous rate maps for the first time. Instead of a single value obtained by previous methods, these two-dimensional instantaneous rate maps contain spatial information on how the molecular outflow rates vary within the outflow cavity.

Multiplying the outflow mass-loss rate with the duration of the protostellar phase, we found that by the end of the protostellar stage, the total mass removed by protostellar outflows is comparable to or even larger than the current mass of the gas surrounding the protostar (protostellar core). This implies that cores must have their mass constantly replenished by mass accretion from the larger scale. With the discovery of a high mass-loss rate from protostellar outflows, the detection of streamers and accretion flows, and evidence of core growth by accretion from the surroundings, raise doubts on the idea of cores as a well-defined mass reservoir. Thus, a well-defined precursor of the IMF is needed to determine the star formation process.

Research Highlight #2: Develop a new method to measure the Protostellar Mass Function

Related Papers: Hsieh et al. in prep.

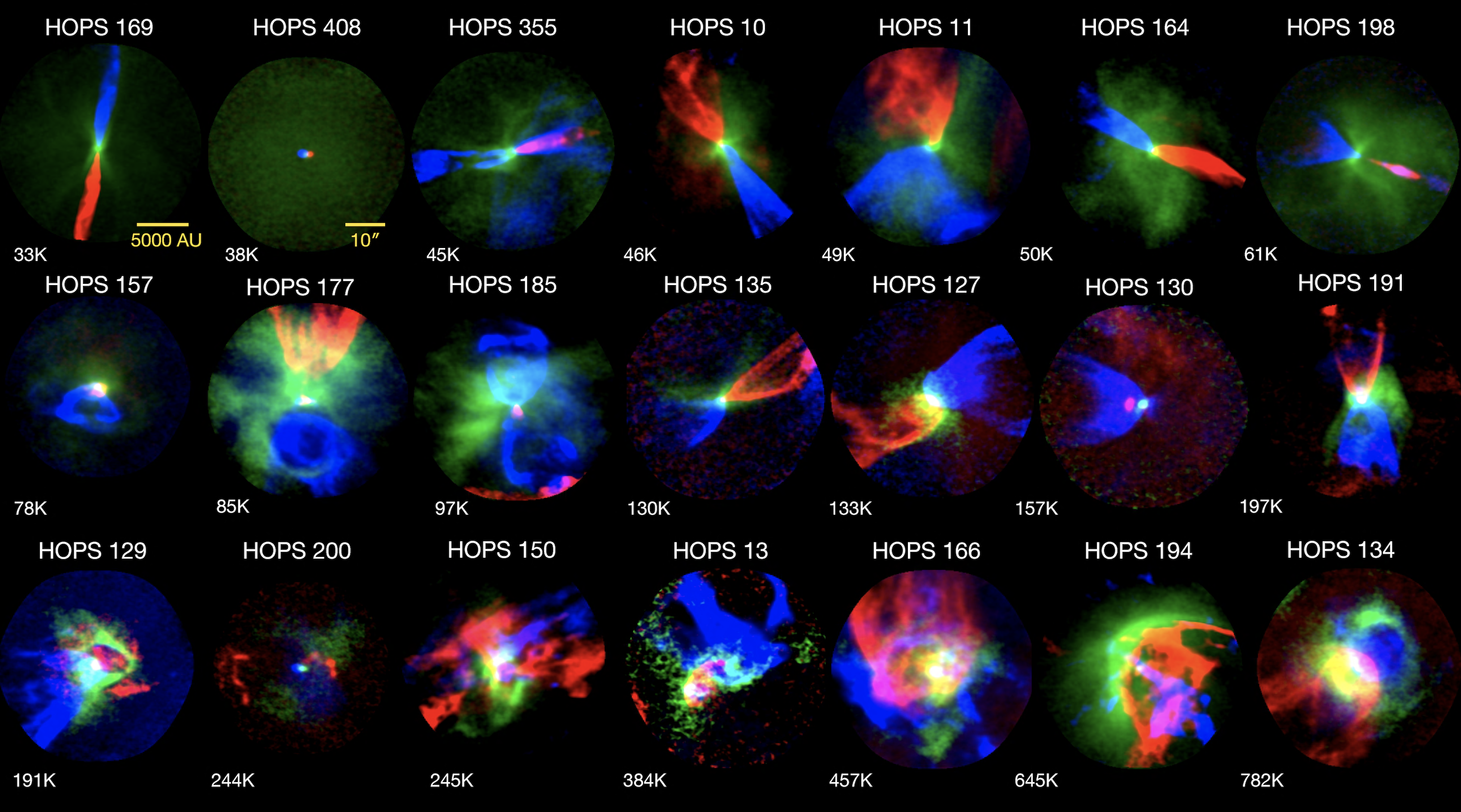

Research Highlight #2: Develop a new method to measure the Protostellar Mass Function During my Ph.D., I tackled the challenge of measuring the protostellar mass function (PMF), a theoretical construct that has yet to be measured [18, 19]. Traditional mass measuring methods relying on fitting a Keplerian rotation curve in circumstellar disks are impractical for building a sufficient PMF sample size in a reasonable amount of telescope time. To overcome this, I devised a novel approach using protostellar jets to estimate the PMF for protostars. I developed a Bayesian hierarchical model that exploited the proportionality between accretion luminosity and the product of accretion rate and stellar mass. This model utilizes the mass-loss rate from molecular bullets within high-velocity jets, which acts as a tracer for accretion from the “primary wind” expelled by the disk. Additionally, we compared the accretion-ejection rate ratio from the Bayesian modeling of observational data with different jet-launching models, such as X-wind and disk-wind models, to constrain the jet-launching mechanism.

Topic#2: Angular Momentum in star formation

Research Highlight #3: How does angular momentum transfer from large to small scales?

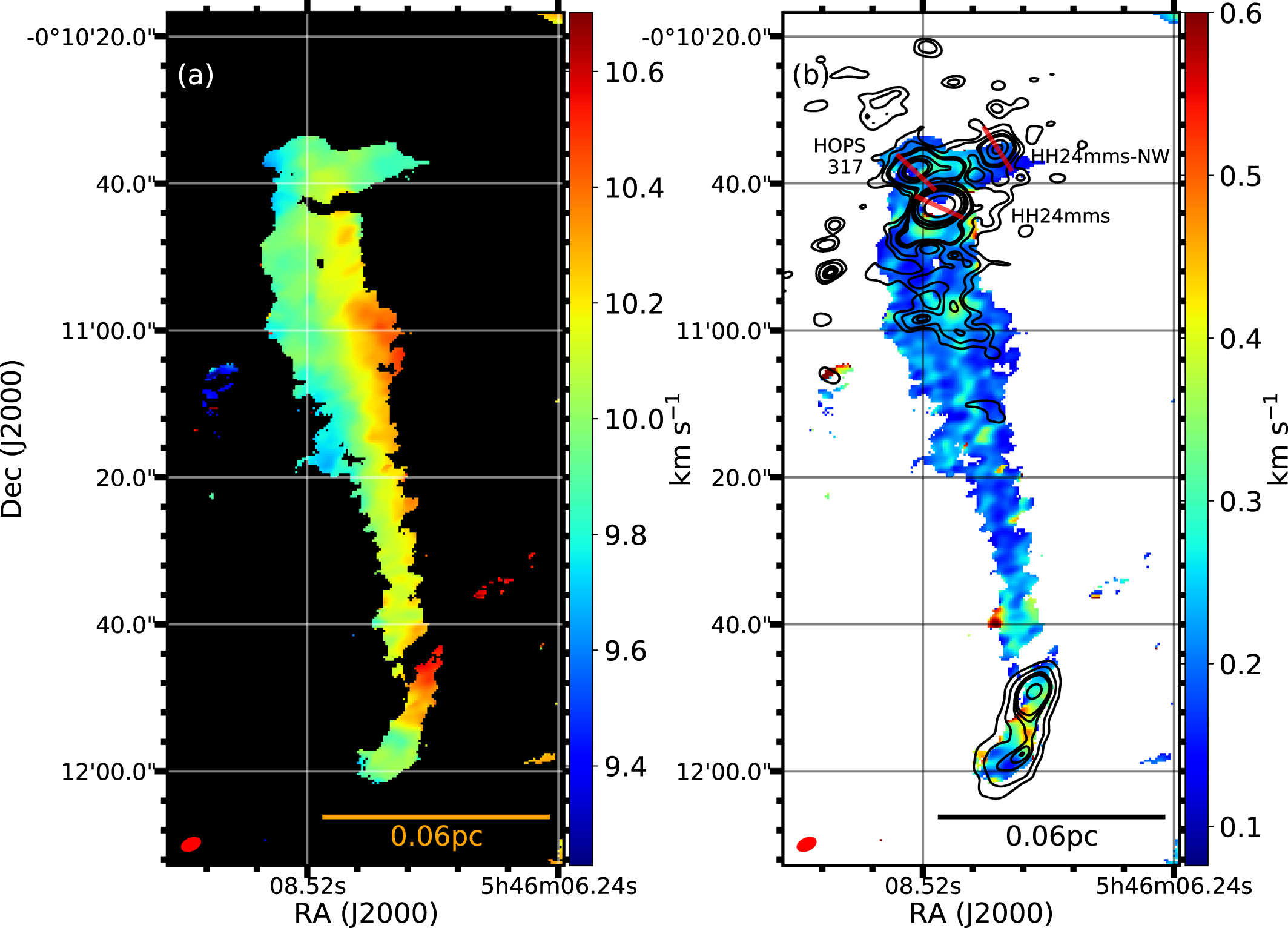

One of the main challenges in star formation is trying to solve the so-called “angular momentum problem,” which arises from the fact that the observed angular momentum of individual stars is much smaller than that of the molecular cloud from which they presumably formed [21, 22]. While specific angular momentum has been extensively studied in cores, disks, and outflows [23, 24, 25, 26, 27], the specific angular momentum study on filaments is missing. During my Ph.D., I have discovered the rotating filament in the Orion B region and conducted the first angular momentum study in a rotating filament at a few 1000 au scales. From our high-resolution N2D+ ALMA observations of the LBS 23 region in Orion B, we find the total specific angular momentum, the dependence of the specific angular momentum with radius, and the ratio of rotational energy to gravitational energy were comparable to those observed in rotating cores of similar size in other star-forming regions. In addition, I found that the angular momentum profile of the filament was consistent with rotation acquired from ambient turbulence indicating cores and their host filaments develop simultaneously due to the multi-scale growth of nonlinear perturbation generated by turbulence.

Topic#3: When do planets form?

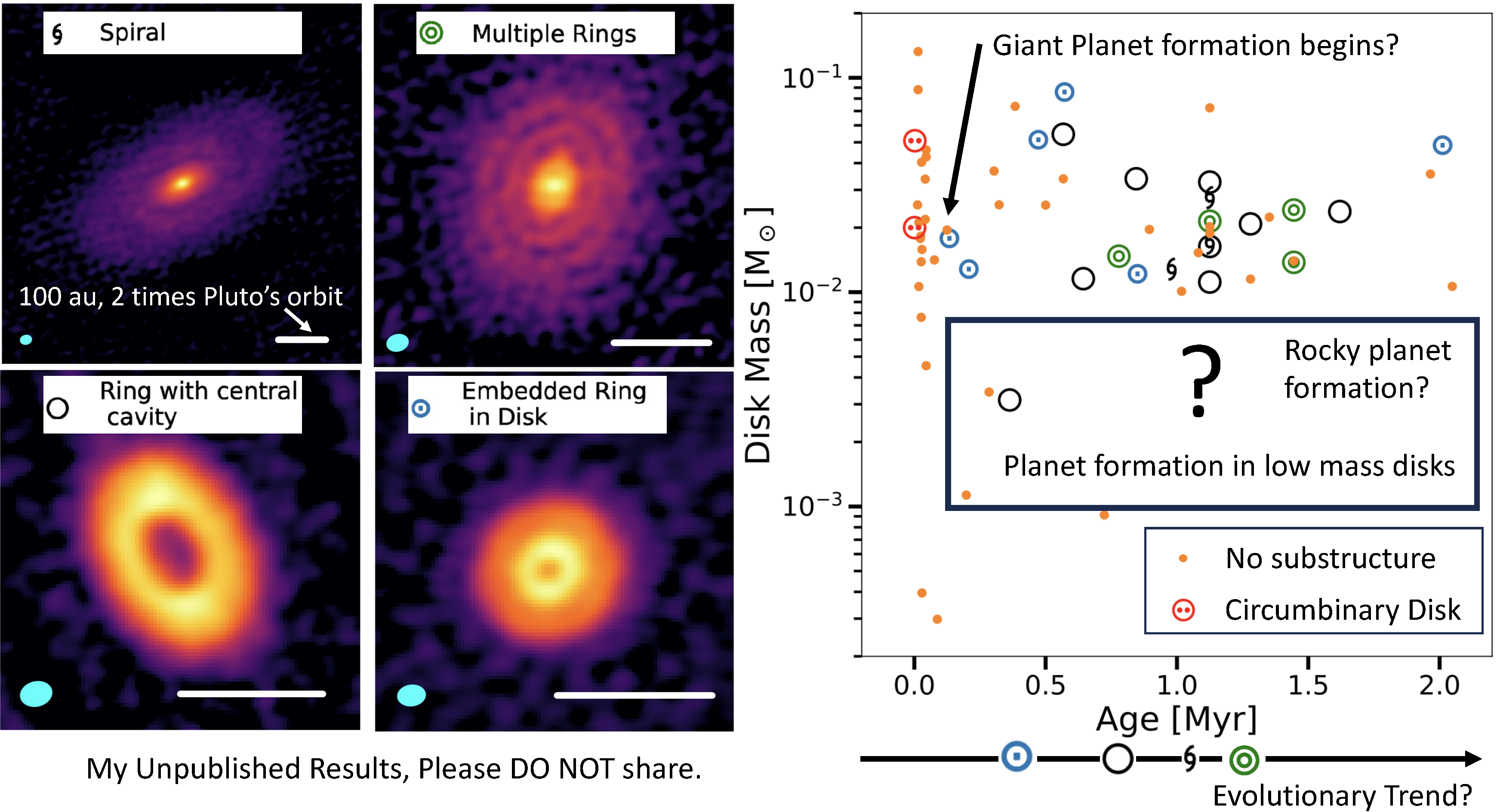

One of the foremost enigmas in the field of planet formation pertains to discerning the relationship between circumstellar disk properties and the primordial conditions of planetary systems. The advent of high-resolution observations by ALMA has fundamentally transformed our understanding, unveiling intricate substructures within disks. These substructures manifest varied natures - some potentially sculpted by pre-existing planets, while others, such as dense rings, may act as nurseries for the formation of planetesimals and subsequent planet generations. However, previous surveys predominantly target large, luminous disks or more mature Class II disks (for instance, DSHARP, ODISEA, and eDisk), leaving an uncharted domain: a statistical study of disk substructures within young Class 0/I sources. This gap in knowledge restrains our understanding of the early formation of disk substructures and, consequently, the onset of planet formation.

Research Highlight #4: The first high-resolution (< 18au) statistical study of disk substructures in young Class 0/I systems (age < 2Myr)

Related Papers: Hsieh et al. in prep. (CAMPOS Data paper)

I am also leading the CAMPOS continuum projects—an ALMA high-resolution (0.1”) continuum survey of the Class 0/I and flat-spectrum sources in seven nearby molecular clouds. We have detected over 180 Class 0/I protostellar disks. Presently, I am preparing at least 2 first-author papers pertaining to the CAMPOS survey: the CAMPOS Continuum Data Release Paper, and the CAMPOS Substructure Statistics Paper. With over 90 disks observed with 15 au resolution, we present the first comprehensive statistical study of disk substructures in young Class 0/I sources. Our exploration uncovered an intriguing timeline of disk development: substructures are conspicuously absent during the Class 0 and early Class I stages, only making their appearance when the protostar attains a bolometric temperature surpassing 160 K, corresponding to an age exceeding 0.3 Myr. Furthermore, these substructures are predominantly observed in disks with a mass beyond 10 Jupiter mass. With our CAMPOS survey, we have pinpointed when disk substructures appear. If these structures are indeed triggered by planets, our findings also shed light on the incipience of planetary formation, enriching our understanding of this complex process.

Topic#4: Interstellar Objects

Research Highlight #5: The origin of the first Interstellar Object ‘Oumuamua

Related Papers: Hsieh Cheng-Han, Laughlin G., Arce H.~G., “Evidence that ‘Oumuamua is the ~45 Myr-old product of a Molecular Cloud” 2021, ApJ, 917, 20.

Image Credit: European Southern Observatory / M. Kornmesser

Image Credit: European Southern Observatory / M. Kornmesser

The 2017 discovery of the first interstellar object ‘Oumuamua fascinated the scientific community, primarily due to its unique attributes such as its elongated shape, unusual brightness variations, and the absence of infrared heat emission as detected by the Spitzer Space Telescope. Adding to the mystery was its significant non-gravitational acceleration.

In an effort to unravel the origins of ‘Oumuamua, I delved into its Galactic trajectory. Intriguingly, this trajectory intersected with our solar system at its maximum deviation relative to the Galactic plane, closely mirroring the paths of neighboring young stellar associations. Employing F-type stars data from Gaia DR2 for comparative analysis, I estimated ‘Oumuamua’s age to be around 35 million years. Further comparisons with nearby moving groups affirmed its congruence with the Carina (CAR) and Columba (COL) moving group, estimated to be approximately 30 million years old. Monte Carlo simulations involving the CAR association revealed that each known star within it would need to eject a mass of approximately 500 Jupiter masses to match the implied number density of interstellar objects detected by Pan-STARRS. This ejection figure is three orders of magnitude higher than the solar system’s planetesimal disk, a contrast that challenges the disk ejection theory. Our analysis, therefore, lends weight to the hypothesis that ‘Oumuamua is a free-floating cloud by-product that originated in the molecular clouds that gave rise to the Carina or Columba associations about 45 Myr ago.

Additionally, I led a large international team as the PI for the ALMA and Green Bank Telescope (GBT) DDT projects to observe the second interstellar object, 2I/Borisov. Our strategy was to trigger joint GBT and ALMA observations in the event of an outburst. We were granted 14 hours of ALMA time and 33 hours of GBT time for this purpose. To ensure continuous monitoring, I established contact with the Las Cumbres Observatory, which would notify us of any outbursts, prompting the coordinated ALMA and GBT observation. I was interviewed by the New York Times for leading the observation. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic enforced a simultaneous shutdown of all telescopes, and we were unable to obtain any data. Regardless, I remain prepared to swiftly assemble a team for future interstellar object observations.

Topic#5: Magnetic Fields in Star Forming Regions

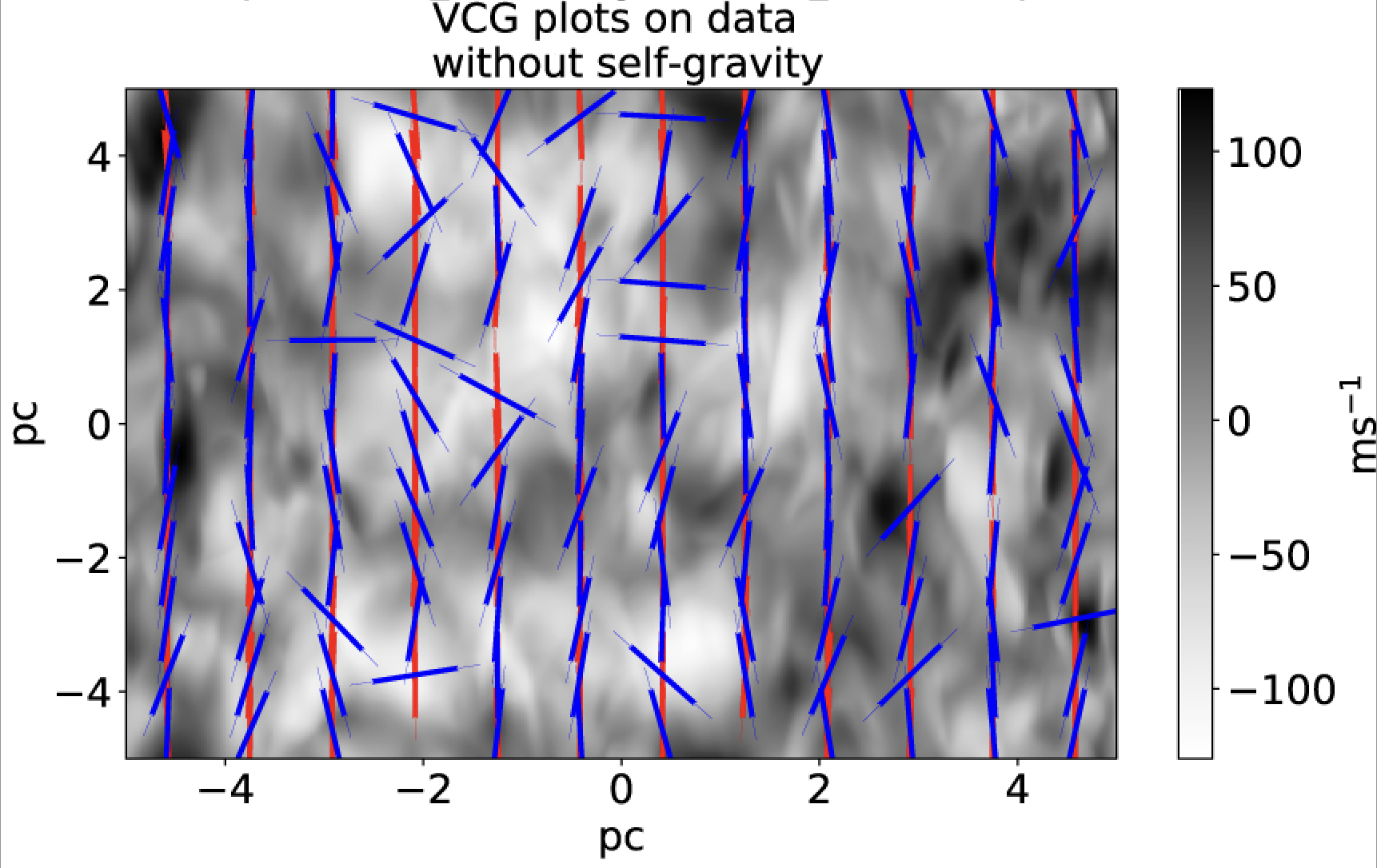

Research Highlight #6: Testing a new method (Velocity Gradient Technique) to measure the Magnetic Field Morphology in the Presence of CO Self-absorption

Probing magnetic fields in self-gravitating molecular clouds is generally difficult, even with the use of polarimetry. Based on the properties of magnetohydrodynamic turbulence and turbulent reconnection, the velocity gradient technique (VGT) provides a new way of tracing magnetic field orientation and strength based on spectroscopic data. Our study tests the applicability of VGT in various molecular tracers, e.g., 12CO, 13CO, and C18O. By inspecting synthetic molecular-line maps of CO isotopologs generated through radiative transfer calculations, we show that the VGT can be successfully applied in probing the magnetic field direction in the diffuse interstellar medium, as well as in self-gravitating molecular clouds.